The Lady Working in a Grocery Store / Danielle Ellis

by David August

A loud noise woke her up, and he woke with her. He could see what she saw: a dirty tent, the mat on the ground where she had been sleeping. He could feel everything she felt, and at that moment, it was mostly fear. People were shouting nearby, their voices filled with despair. One of them cried out her name.

Another terrible noise shook the ground. The bright light temporarily blinded her, so he couldn’t see either. When she opened her eyes again, there was fire everywhere. He choked on the smoke along with her as she struggled to find a way out. But the tent was made of cheap plastic; once it caught fire, there was no escape.

Now, he was stumbling barefoot through the debris, dragging a bucket and searching for water. He laughed at something one of his friends did, and before long, they were all laughing. Distracted as he was, he didn’t noticed the sniper aiming at them from a distance. A precise shot to the head killed him on the spot. The other presence, still confined to his body, had to stay there until the next jump.

Before he knew it, he was on a beach, walking fast and trying to keep up with his father and uncle. A few paces ahead, his father glanced back and yelled, “Hurry up!” His words had barely left his mouth when he vanished into a cloud of smoke and sand.

The blast knocked him down, but he quickly got up and started running. Survival instinct was the only thing driving him forward. His mind had yet to process what had just happened or register his injuries.

He didn’t pause to check if his father was with him, never doubting that he was. But the silent witness inside him, connected to every sensation, knew otherwise. As an experienced veteran, he could identify the drone hunting them down without looking at it. He knew exactly how many seconds it would take to adjust the targeting system for the final strike. He was not wrong.

More final moments kept coming. Being operated on without anesthesia and not surviving. The roof collapsing after the building was hit by a missile. Another sniper shot. Another bombardment. Then another, and another, and another. He couldn’t shut himself off from any of them. He had been able to before, but now it was impossible.

At last, the commander made it back to his hospital bed. He had lost count of how many times this had happened, though he still remembered how terrified he had been when he first arrived. Cancer had finally caught up with him, the one enemy he had never been able to eliminate. Now, however, returning to this sterile room was a relief. It was the only place where he could be himself and face death alone.

A man in uniform was sitting on the couch near the bed. In a feeble voice, the patient asked, “How many more?” The lower-ranking officer stood up quickly and said, “Sorry, General, what did you say?”

“In that last campaign, how many?” the sick man said with difficulty. “How many children did my division kill?”

The other man, who happened to be the general’s nephew, went from looking worried to looking embarrassed. In a soothing tone, he said, “Don’t think about that now. You should try to rest.”

The general narrowed his eyes and demanded, as forcefully as he could, “How many?”

His voice lacked any hint of his former authority. It was only his nephew’s desire to prevent the ailing man from overexerting himself that prompted him to say, “There were twenty unfortunate victims. All accidents, of course.”

“Not the official number, damn it,” the general said. “The real one.”

The junior officer chose to ignore the question. As he turned to sit down again, his uncle grabbed his hand. “How many?” the general insisted, refusing to let go despite having no strength left.

With the utmost reluctance, his nephew replied, “Five thousand.” It was not the correct number – he couldn’t bring himself to say that – but rather a modest estimate.

“Five thousand,” the dying man repeated, bracing himself for another jump. “Five. So … maybe four. Maybe four thousand to go.”

David August lives in São Paulo, Brazil, and works in human rights advocacy. His stories have appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Bright Flash Literary Review, and The Rumen, among others.

Centerpoint

After checking Facebook, Instagram, and Tiktok for the 200th time that morning, she decided she needed that new miracle drug. Ozemplic for the brain. She needed to take control.

Yes, the injection started out as a cure-all for another terrible disease: obesity, which was a detour from the original intention to treat diabetes. But researchers had discovered that it also curbed one’s use of the Internet by taking away all interest, as it were, slacking the appetite. The addiction to constantly checking, then after checking the endless scrolling, the doom-scrolling where one sucks up all the bad news like a vacuum cleaner in a black hole. The obsessive looking at the screen of her phone, actually not letting go to put it down, holding it as if it were a talisman against . . . What?

She didn’t know, but she would Google right away. What am I afraid of?

Sometimes, late at night, she’d awake or—more often than not—she’d been unable to fall asleep—and type into her Kindle Fire by the bedside: Tell me the future. Once she asked the universe, more specifically: What is that blurry thing off in the distance that looks like trees waving in the wind? And the ChatGPT came up with an answer: You’re off your rocker.

That’s how it felt. Askew. Does anyone ever use that word anymore? Yes, bounced the bot. 9006884 times a day.

It was her phone that recommended Ozemplic.

The rectangle dinged one morning, and she jumped out of the shower to see a message. She quickly toweled off and sat on the couch wrapped up with nothing else on, rivulets streaming from her head and onto the device screen. Finally someone cared enough to reach out and help. Or something. Never mind.

When did it start? Was it after the unexpected passing of her mother at only age 54? One day she was great, the next she was in the emergency room, and two weeks later dead. Didn’t the universe know that even though she—a college graduate in an only okay job but more importantly with health benefits—perceive that she still needed support. To be able to call her mother up and complain. If her mom called her, she’d complain that she was calling. “I need space, Mom,” she’d say. Well, guess what! She got space and so much more. Loneliness. Now no one calls.

Not even her brother, who disappointed the relatives and her biological father by coming out trans and wearing a dress to the graveside service. He’s got his own fish to fry (according to Grandpa). Her family was too busy with their own stuff to ask what’s up with her. She was considering getting a rescue cat, except she was allergic to fur.

This drug was her chance to get back her life, seize agency, move forward. Despite the side effects.

Dry mouth.

Dry eyes.

Dry vagina. (Oops, maybe this one, but no—there were creams to fix that)

Dry heaves.

Weight loss.

Loss of interest.

Love loss.

Lost (the TV series)

Streaming.

Stream of consciousness.

This was a partial list. She made an appointment

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

No longer storming out of the shower to the sound of her phone, no longer binging on social media, she was dry. Empty. Her days devoid. From, you name it. Packages of Perfectly Pickled Pups from Trader Joe’s, bread rolls with flakey salt, take out from Ms. Egg Roll. The freezer and coffee table were wiped clean.

The desire for coffee suddenly diminished. She lost the remote for the TV. No more Lost.

Her mornings were a blank slate with only the sun peeking, peeping, creeping across the length of the floor. Toward the bonsai garden, where she daily rakes the tiny pebbles with a miniature rake. Her Word-a-Day calendar introduces palimpsest. A manuscript or piece of writing material on which the original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing but of which traces remain. Truth, she thinks. There are traces, but, at the same time, room for new. She ruminates, Life is every bit like this. Palimpsest.

There’s the morning walk to her car which she never noticed before. The birds that gather in a tree adjoining the bank parking lot. The tree itself, changing according to the seasons. She remarked to the new guy at work, the one glued to his phone in the break room, that the tree was aflame with autumn gold. And he said, What tree?

But later, after work, they both stood in the parking lot and watched the leaves dance the mazurka in the evening breeze. And, even later that month, they drove to the forest preserve with lawn chairs to catch a late afternoon symphony.

Nothing happened. Nothing at all.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jane Hertenstein is a Pushcart nominee whose work has been recognized by the New York Times. She is the author of over 100 published stories both macro and micro: fiction, creative non-fiction, and blurred genre. In addition she has published two MG novels and a non-fiction project, Orphan Girl: The Memoir of a Chicago Bag Lady, which garnered national reviews. Jane is the recipient of a grant from the Illinois Arts Council. She teaches a workshop on Flash Memoir.

Brother Amos said last Sunday that the heat during the summer is God’s reminder of what sinners feel in H-E-Double-L. He’s the type to think up catchy sayings — stuff adults want to write, words people can live by.

And he’s right. Outside is miserable, even in the mornings, and it gets worse throughout the day. Despite the constricting air, there’s a palpable energy. Green is everywhere, covering the lattices around the church, scraping up towards the sky. Crops in the outer parts of town thrive, waving to you on your walks.

Imagine the sensation of growing towards the sun. Imagine the greed.

Your normal routine stays the same — walking Gibson, taking care of the garden with Mom, pretending to go to sleep every night at 7:30 like you’re supposed to, even though it’s still light out.

Mom says you’re getting bigger, about to be a teenager, so you have to wear even more. With each change in your body, there’s an extra layer. A training bra for your chest, an added wrap for your shoulders. Even in the dead of July, you wear a cardigan when you step out of the house. She still tries to pull your neckline up to the top of your throat, as if you should be ashamed of its shape and line.

Schools in the county are out. In the town next door, teenagers swarm the Walmart, the Piggly Wiggly, the McDonald’s until they are bored. With nowhere else to go, groups of them drive into Pine Grove and wheel around, taking their sweet time on the easy road towards the lake, curved to what you imagine is perfection by the town’s founders.

You watch them sometimes, when you can, as they trot in and out of the corner gas station, wearing their shorts and tank tops, tanned skin, and lake water hair. The gasoline tank in your hands threatens to tip onto your skirt, and you hug it to your chest. They’re laughing, one holding a bottle of juice that could dye fabric, and the sight sends spit to the back of your mouth. The drink is what rubies taste like, maybe.

They don’t look twice at you.

To study them, their mannerisms and their language is to experience something close to envy. Wanting what they have, what they enjoy but don’t care to share, and knowing it’ll get you set on fire, eternally. It aches though, iron knitting into your stomach.

“Is being jealous a deadly sin?” you ask Dad, swinging your feet at the kitchen table. A sheet of too-easy math drills lies neglected in front of you. Though county schools are out, your school never stops, ticking on and on throughout the year.

Dad puts his steaming coffee on the table. He scooches his foggy glasses up his nose to rest on his hairline. You watch him and get the strange sensation of seeing him eye to eye. His squint gives him a rodent look, his features small. You don’t lock into his stare, fear bubbling inside your head.

“Well,” he starts the lecture. “Evie, the Bible condemns envy as a deadly sin. And jealousy is another word for it. So what do you think?”

You hate it when he makes you parse things out like this, everything a teachable moment. Placing your hands in your lap, you parrot the last Sunday School lesson. “When we do a deadly sin we have to repent.”

“That’s right. Have you been jealous?”

Your chest expands, contracts. Past whoopings dance in your head, visions more than memories, all hateful. “I don’t think so.”

“You don’t think so? If there’s a chance you could sin, darling, you need to confess it,” Dad says. He moves his glasses to his nose, crosses his arms and pulls his chair back. The distance is like a mile.

To confess would mean absolving yourself of it, of making idols of the secular life, the teenagers and their clothes and their privileges. God would forgive you if you confessed.

But it means that you’d get bent over your bed again, and you’ve never taken to the belt before, so you won’t start now. It always just made you angrier, greedier, uglier inside.

Maybe that’s you. Maybe you were always an ugly thing, this emotional mess. You can’t tell one from another, mixing sadness with sloth and curiosity with lust. At the last youth meeting, Brother Amos said that most people start to sin in their teens and keep going until they die.

Decide now. Tell Dad whatever you can get out of your mouth. Confession or not, it’s not gonna change a thing.

“I haven’t,” you say. Confidence comes out of you as Dad nods to the words. He’s looking at you through his eyebrows now. “I’m just worried about Josie from Sunday School. She said she was jealous of the boys.”

He hums. “Why is that?”

“They went outside and played football,” you say, hopeful that he won’t slap your wrist for stammering. “And we stayed for another lesson.”

“You shouldn’t be around that Josie,” Dad says. “Envy is the root of many evils.”

As he lifts his coffee back in the air, you sit, numb. In one sentence, you’ve disobeyed Dad and the laws of God, like plucking a blade of grass between two fingers: curious, probing. He couldn’t tell you were lying.

Does that make you a liar? Is this what Brother Amos means when he talks about little add-ups in your life?

You go back to your math drills, jotting down numbers, your brain half-on and your attention set everywhere but the kitchen table. In the corner window, a fly buzzes, knocking itself against the glass. If you stare real hard, you can hear each individual wing flap.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………End

M. Anne Avera is an author, poet, and teacher from Auburn, Alabama. Her debut collection of poetry, “Complete and Total Honesty” is available now through Neon Origami Books. You can find out more about her at writeranneavera.carrd.co

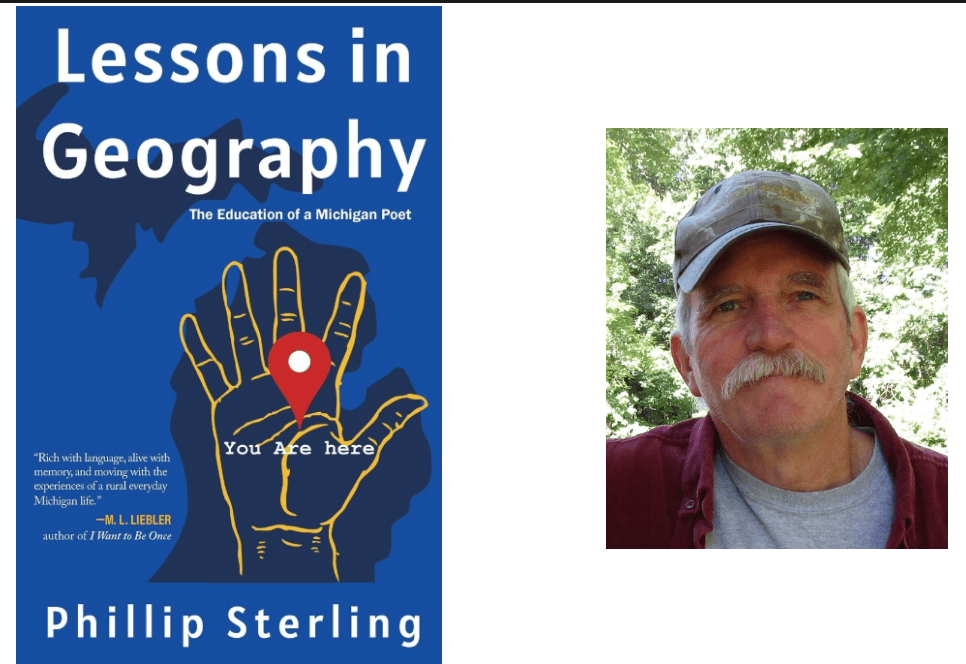

Written and published over a period of forty years, the essays in Phillip Sterling’s Lessons in Geography chronicle how his formative years in Northwest Lower Michigan not only inspired him to be a writer but also profoundly influenced his creative and critical perspectives. Diverse in form, the essays are nonetheless unified in theme: how the geography of a place—the forests, shores, and lakes of Michigan—plays a role in one’s education, imparting knowledge of the wider, human world.

Phillip Sterling is a poet and fiction writer. His books include Mutual Shores (2000), In Which Brief Stories Are Told (2011), Amateur Husbandry (2019), and Local Congregation (2023). He is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry, two Senior Fulbright Lectureships (Belgium and Poland), a PEN Syndicated Fiction Award, and artist residencies at Isle Royale National Park and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He lives in Lowell, Michigan.

Phillip Sterling was born in the metro Detroit area and raised largely in rural West Michigan. Like earlier Michigan poets/essayists such as Theodore Roethke and Jim Harrison, Sterling, in these lovely essays, explores both the external and interior dichotomies of settled/unsettled and domestic/wild. And like his predecessors, Sterling manages to convey genuine, moving sentiment without becoming sentimental. This is a book about a poet’s sometimes perilous coming of age, and of aging with grace and acceptance. —Sue William Silverman, author of Acetylene Torch Songs: Writing True Stories to Ignite the Soul

Whether writing of his northern Michigan boyhood, ancient trees, Mom’s custard pie, dog bites, Belgian frites (French fries), or the abandoned death camps of Poland, Sterling brings wide-ranging insight, an in-depth sense of history, self-effacing wisdom, and the marvelous double vision of the true memoirist to these essays. His “lessons” build chronologically to depict the development of a writer’s imagination with the deftness that marks his signature poetry, both complex and captivating. This fine work is a significant contribution to the Great Lakes “Voice.” —Anne-Marie Oomen, author of The Long Fields and recipient of the 2023-24 Michigan Author Award

In Lessons in Geography: The Education of a Poet, Phillip Sterling distills a lifetime of lessons learned in places as varied as an “Up North” Michigan lakeside cottage, a Kentucky college mailroom (where a mysterious sketch and message on a paper bag affirm his identity as a poet), and Liege, Belgium, where he explores the nuances of “mutual understanding” in light of Belgian kissing customs. Whether describing the “roguish” appeal of black licorice or dissecting a recipe for stollen, ingredient by memory-laden ingredient, Sterling mixes keenly observed experiences with fresh perspectives, all rendered with a poet’s sensitive precision. The result is a memoir that transcends mere recollection. —Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, author of Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta

Phillip Sterling is one of Michigan’s finest and best known poets and fiction writers. In this new collection, he raises the non-fiction bar to a new level. These wonderfully crafted essays are rich with language, alive with memory, and moving with the experiences of a rural everyday Michigan life. I highly recommend this book. Lessons in Geography is one of the most engaging and accessible memoirs I’ve read in recent years, a beautifully written narrative about place and the poetry it inspires. —M. L. Liebler, Detroit poet, editor, and author of Hound Dog: A Poet’s Memoir of Rock, Revolution and Redemption

Talia Cutler attends Trinity College majoring in English Language and Literature. She hails from East Coast soil – the metamorphic stuff and continental margins, not the sandy parts. She often writes herself into corners and is in pursuit of things that are beautiful, such as large bowls of apples, crosswords, and the Blue Ridge Mountains. She has previously been published in Rainy Day Cornell, The JAR, and has won two Scholastic Writing Awards. She enjoys em dashes, oxford commas, and David Foster Wallace.